As a film manufacturer, Kodak’s role in America’s development of the atom bomb might seem unlikely. But this new book tells the story of how film manufacturers on both sides in WWII became integral to their nation’s war efforts, ushering in the age of nuclear weapons and the Cold War that followed.

From the moment you trip the shutter to the moment you pull the developed negative out of the tank in the darkroom, the capture of an image on photographic film is, first and foremost, a chemical process. Grains of silver halide suspended in an acetate emulsion capture the light; chemical developer transforms these exposed grains of silver salt into visible, metallic silver; and finally, a fixer solution is applied to dissolve and remove the unexposed silver halides. The result is an image recorded in the film emulsion as tiny specks of metallic silver.

All of this chemistry might seem a million miles away from the kind of technology needed to develop a nuclear weapon, but it may surprise you to learn that the manufacture of a roll of photographic film and the manufacture of the explosive core of an atom bomb actually have more in common than you might think.

This brings us to Alice Lovejoy’s new book, “Tales of Militant Chemistry: The Film Factory in a Century of War,” that is scheduled for release on August 26th.

At the core of her book, Alice Lovejoy tells the fascinating and largely untold story of how the U.S. Department of War approached Kodak during World War II and sought its help with its top secret Manhattan Project to develop an atomic bomb. There was great urgency surrounding this project at that time. It was believed that Nazi Germany was also well on the way to making a nuclear bomb, and the consequences of allowing that to happen before the Allies had developed their own weapon were too terrible to contemplate.

As a manufacturer of photographic film, you might wonder why Kodak, of all companies, would be sought out by the U.S. military to help develop an atomic bomb, but there were a number of factors that made Kodak an ideal partner for this.

Firstly, the Kodak Company was no stranger to war production, having provided resources and materials to the military during World War I that were essential to the war effort. These included not only the kind of film and equipment needed for aerial reconnaissance photography that you might expect but also a host of other resources, including the varnish or “dope” applied to the canvas airframes of military aircraft—a product that was derived directly from Kodak’s own work to develop better film emulsions.

Secondly, the effort to build the first atom bombs required a massive investment in chemical manufacturing in order to generate the enriched uranium fuel needed for an atom bomb’s explosive core. The scale of the manufacturing infrastructure that would be needed was unprecedented for a wartime project, and this kind of large-scale manufacturing was an area in which Kodak excelled. As Alice Lovejoy demonstrates so vividly and insightfully in her book, if you take a step back and look at the ways in which photographic film and atom bombs are manufactured, these might seem like very different products. However, the essential operation at the core of their manufacturing processes involves the massive acquisition of natural resources and their chemical transformation into specialized, man-made compounds engineered with a unique set of qualities for a specific purpose.

The acetate base of photographic film emulsion is derived from cellulose extracted from large quantities of wood pulp or cotton and chemically modified so that it can be extruded into thin sheets to make rolls of film. The fissionable uranium enriched with the uranium-235 isotope must be extracted, practically atom by atom, from tons and tons of uranium ore that consists mostly of the unusable (for nuclear weapons at least) uranium-238 isotope.

Eastman Kodak Company factory and main office in Rochester, New York, circa 1900 (courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The truth about the race to acquire these natural resources is sometimes far from pretty. One of the darker chapters in the book describes the horrific conditions under which the Congolese people were forced by Belgium’s colonial government at the time to mine the uranium ore from their country’s abundant deposits—a great deal of which would eventually find its way across the Atlantic to the massive uranium enrichment facilities created for the Manhattan Project.

This brand of inhumane exploitation for the purpose of extracting and processing natural resources is also something of a recurring theme in the book. While Kodak was becoming an integral part of the American war effort, the AGFA (Aktiengesellschaft für Anilinfabrikation) film corporation in Nazi Germany was pressed into the service of the German war effort, becoming a part of the notorious IG Farben industrial cartel that used concentration camps and slave labor to manufacture so many of the materials that Germany needed to maintain its war machine.

Like Kodak in the U.S., AGFA’s chemical expertise would also be leveraged for the production of detonators and explosives. Over the course of the conflict, many of the bombs, artillery shells, and hand grenades exchanged between the Allies and the Axis powers would contain components that had been manufactured by Kodak and AGFA—a far cry from the kind of products these companies had been producing during peacetime.

Another very interesting aspect of the Manhattan Project that I learned from this book is the largely untold story of the enormous role that women played in the race to build the atom bomb. In fact, the great majority of the workers who operated the vast uranium enrichment facilities that Kodak ran at Oak Ridge in Tennessee were women. Many of these women did grueling jobs that required hours of sustained and extreme focus in order to keep production running, and the women who were trained for these roles were highly prized for their tenacity, patience, and attention to detail.

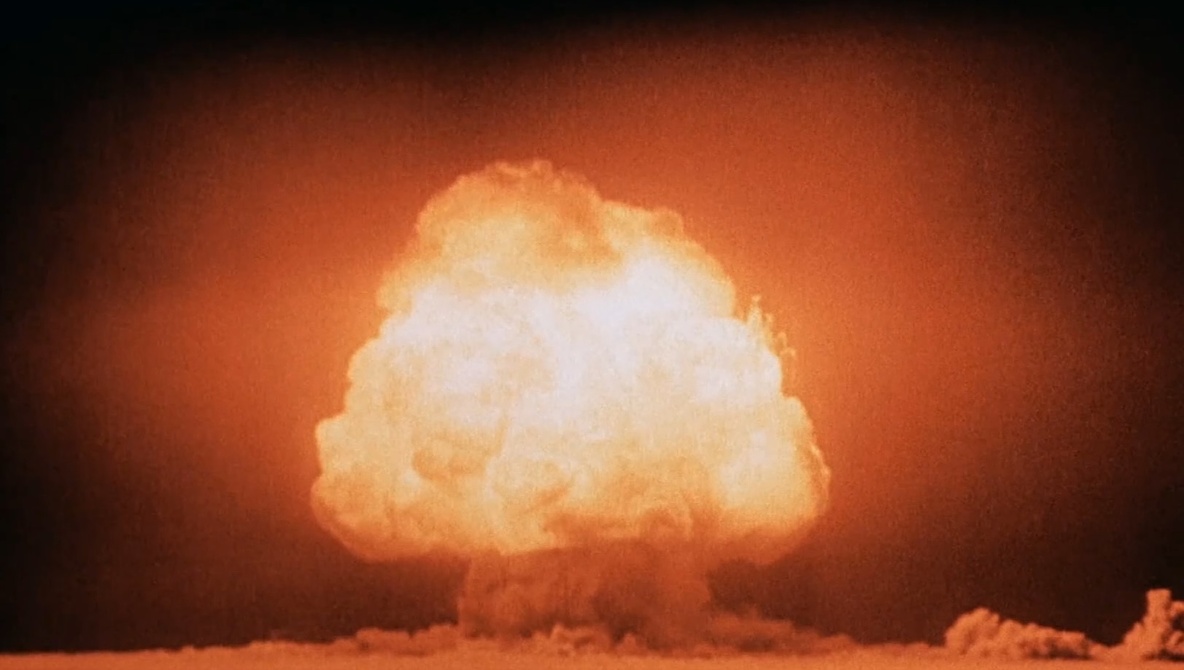

Following the surrender of Germany and its allies in Europe, it would be the atomic bombs developed by the Manhattan Project that would write the final chapter in the global conflict and finally bring the war to an end. After testing the first atomic bomb at Alamogordo in New Mexico (with more than 50 cameras present, all loaded with Kodachrome film to record the event for posterity), the weapon would be used against the Japanese over the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The bombs effectively leveled the center of each city, killing hundreds of thousands—many of them perishing immediately in the split second following the weapon’s detonation.

With the dawn of the age of nuclear weapons and the Cold War that followed, Kodak was once again a company primarily manufacturing photographic film as it had been before the war, but it would find it difficult to shake its nuclear legacy. In a major twist of irony, as the U.S. embarked upon decades of nuclear weapons testing, the radioactive isotopes that Kodak had once helped manufacture were now being released into the atmosphere to be driven east across the Midwestern plains by the prevailing winds—eventually to fall from the skies around the Great Lakes and turn up in the very water and the wood pulp that Kodak used to manufacture its film emulsions and its packaging. These radioactive particles would reveal themselves in the form of small spots and fogging on unexposed film—the photons of ionizing radiation triggering the chemical reaction of the silver halides in the emulsion just like the photons of visible light that they were designed to capture. Starting with the Trinity test, in which the very first atomic bomb was detonated at Alamogordo in 1945, through all of the subsequent decades of nuclear testing, the Kodak factory in Rochester, NY would become the proverbial canary in the coal mine for the radioactive isotopes that mankind was putting into the atmosphere through its testing of nuclear weapons.

There is another pretty amazing footnote to this incredible story. In 2023, Christopher Nolan, the Hollywood director who would undertake the considerable feat of bringing the story of the Manhattan Project to a wider audience, would, in an age dominated by digital media, choose to do so using Kodak’s 70mm film. This film stock was based on the exact same cellulose acetate manufacturing process that originally brought Kodak into the Manhattan Project all those decades ago.

There are many more such fascinating twists and turns in the historical narrative of this compelling and extensively researched book. As a lover of film photography and history, I found "Militant Chemistry" to be a riveting read, and I would have no hesitation in recommending it to anybody who loves history or just great storytelling. Despite the technical nature of its subject matter, Alice Lovejoy never lets the story get bogged down in technical detail, sharing only enough of it to keep the story moving along while also giving the reader a firm grasp of what is happening.

At the end of the day, this is a story about the transformative power of chemistry and how those who are able to master its subtle magic can change the world. Until I had read this book, it had not occurred to me that the chemistry required to make a roll of photographic film or an atom bomb had more in common than you might imagine. Take an elemental metal and combine it with a halogen to make a metal halide, and you can create a light-sensitive surface on which you can record an image of your town bathed in bright sunlight—or you can create an explosive metal core that could incinerate that same town in a blinding flash of light.

Something to ponder next time you are pulling your negatives out of the developing tank.

Alice Lovejoy’s “Tales of Militant Chemistry: The Film Factory in a Century of War” will be available to purchase on Amazon on August 26th.

It’s interesting to learn the history that photography companies played in various countries’ war efforts. It’s… depressing to see the results, both then and now.

Occasionally there are more hopeful stories, such as the “Leica Freedom Train” that a couple of the Leitz’s used to save several hundred people from WWII’s holocaust

Thank you for this detailed preview. This looks like a fascinating book, and I've preordered a copy.

One statement in the article that I found particularly interesting was, "With the dawn of the age of nuclear weapons and the Cold War that followed, Kodak was once again a company primarily manufacturing photographic film as it had been before the war..." Having not yet read the book, this statement seems to reflect Kodak's singular focus on wet-chemical photography and physical images, foreshadowing the corporate inertia that would ultimately doom Kodak when photography became digital and image sharing went online.